Holly Masterson jewelry uses ancient artifacts and skilled craftsmanship to create jewelry with a bold yet refined aesthetic. New pieces include lapis, jasper and pearls, as well as old bone and shell. Shop the latest jewelry online.

Author Archive

New Designer: Common Projects

Immaculate is one way to describe Common Projects shoes. In 2004, Flavio Girolami and Prathan Poopat started the company as a singular collaborative project to create their idea of a perfect sneaker. The two, living in two separate countries, Flavio in Italy and Prathan in New York, had been friends in the fashion industry years prior. Despite having no experience in shoe design, their industrial and graphic design backgrounds combined without being hindered by convention, played to their benefit.

Their goal was to deconstruct the essence of a sneaker and create a simple and utilitarian shoe made with high quality materials and craftsmanship. Having shoes that are suitable for comfort while also being sophisticated enough to be dressed up.

Inspired by the lines of everyday objects, their first shoe was the original “Achilles,” a clean laced low-top sneaker available only in white, grey or black, branded by ten gold numbers at the heel. This design has remained their best-seller and the ten gold numbers, which denotes the style, size and color, as their only signature.

Shop Woman by Common Projects

Officine Creative Sandals for Summer

Handmade in Italy, Officine Creative shoes offers refined Italian craftsmanship combined with authentic and distinct character. For summer, Workshop in Santa Fe is carrying new metallic finishes on popular styles, such as the Itaca, a leather crossover flat sandal. Shop the collection online.

Introducing: Miao Ran

Miao Ran is a sophisticated brand with an edgy twist based in Milan, Italy. Over the last two years, the brand has established a recognizable style both in menswear and womenswear. Represented in more than twenty shops all over the world, the brand is known for its crafty approach, liquid silhouettes and intricate details.

Miaoran is focused on profound fabric research and sustainability.

Born in China, the creative mind behind the brand studied Design and Pattern Making in some of the most prestigious Art and Design Schools in Europe. After an intense collaboration with Missoni, he chose Milan as the place to establish his brand in 2015. His talent was immediately noticed by Mr Giorgio Armani who supported his spring summer 2017 fashion show at Armani Teatro.

Miao Ran’s philosophy is based on personal approach and customization of every garment produced under his label. He believes that the clothes are a container for the body, male and female.

Introducing Boboutic

Introducing Boboutic

Conceptual knitwear

When we think knitwear, we often think of the garments that supplement an outfit rather statement pieces — the thin undershirt, the tights below a stunning dress, or the pullover sweater for an afternoon at home. Knitwear has been confined to essential, yet uneventful apparel. Boboutic’s mission rejects this quotidian notion of knitwear.

Founded in 2000 by designer Michel Bergamo and architect/photographer Cristina Zamagni, the collections are conceptually driven and inspired by the complexities found in everyday experiences. Rock mosses and lichens guided the spring/summer 2015 collection of sculptural verdant and cream-colored garments; the impression of “taking cover” drove the layered, voluminous pieces from last year’s fall/winter 2017 season. With “…designers [who] consider knits an ideal medium, since its versatility allows conceiving unique surfaces and unexpected shapes,” and extending this medium through a “constant research for new materials and production methods,” Boboutic is on the forefront of reconceptualizing knitwear as a platform for sartorial innovation.

Fabrication of knitwear

The designers at Boboutic take a closer look at the baseline essence of knitwear, which is defined by the garment’s method of fabrication and the architecture of the threads. At the base of almost all textiles is yarn: a line of material ranging from ultrafine polyurethane threads to thicker strands of natural wool or even paper yarn. Knits are distinctive in that the yarn is an endless line that follows a meandering, interlocking path through the entirety of a garment, where wovens are a series of crossed yarns that generate a grain within a textile. The ends of wovens must be finished; knits are endless.

Interlocking loops within knitwear create complex topologies. Unlike the straight, vertical / horizontal foundation of wovens, knits are founded in the yarn’s looping path along a row, interlocking with loops of rows above and below. Interlocking loops create an intermingled, architectural network. Because there are no straight lines of yarn in knitwear, garments are capable of stretching movements and multi-directional pulls. Knitwear is therefore flexible, easily constructed into small detailed pieces, and capable of retracting into shape rather than wrinkling after being folded. This allows for much versatility in the construction of knitwear, providing the designers at Boboutic with room to explore materials used in the fabrication of the yarn.

New and innovative materials

There is a high interest in materialiality with this spring/summer 2018’s Compendium Collection: inspired by paper with the promise of a silky, comfortable touch. Yarns used in the various garment designs range from fine Makò cotton, to coated cotton, to paper yarn.

Makò cotton is the Egyptian variety of high quality cotton. The extra-long staple fibers (ELS) occurring naturally in certain species are what constitute high quality cotton; the result is superior strength and thread uniformity. Because a very small percent of high quality, extra-long staple cotton exports come from Egypt, garments made from Makò cotton are somewhat of a rarity. The Makò cotton used in the Loose Knit Sweater, A-Line Jacket and the Shirt/Jacket pieces make for a fine texture and a flexible, breathable finish.

A favorite fiber, Boboutics innovates with modern poly-coated cotton yarn. Polyurethane coating creates water-resistance, durability, and enhanced visual properties. The polyurethane-coated cotton yarn interlocks with layers of synthetic polyamide strands (created through a melt-spinning process) in the Textured Duster Coat and Textured Short Jacket pieces that are inspired by the texture of watercolor paper.

There are implicit and direct relationships with paper throughout this collection. We see the direct connection through the use of paper textile (or carta tessile) in the Paper/Cotton Dust Coat and Paper/Cotton Open Jacket. Nothing like a garment made of paper, these pieces more closely align with the concept of shifu, a Japanese woven cloth made with hand twisted paper yarn in weft and yarn of another material, such as cotton, in warp. Unlike woven shifu, Boboutic’s knitwear pieces make use of a single, endless line of interlocking paper yarn that creates an interior panel layered between two outer panels of knitted cotton yarn. The effect is a three dimensionality, an illusory essence of reflectiveness in the surface, and a fascinating degree of flexibility. The meandering nature and movement inherent in knitted yarn is apparent in the flexible interlayer of these carta tessile pieces.

Conceptually-driven collections

Boboutic’s knitwear collections are conceptually driven and inspired by the complexities found in everyday experiences, with romanticism interlaced into the way the garments are crafted and understood. This spring/summer 2018 knitwear collection takes its name from the concept of Compendium, defined as “a collection of concise but detailed information about a particular subject,” paper being this season’s particular subject of interest.

The Boboutic Compendium Collection for spring/summer 2018 “can be interpreted as a progressive blow up of a piece of paper. Beginning from the rigorous, compact appearance of a distant look, step after step, article after article, the eye penetrates ever deeper into the page, finally arriving to lose itself in the grid of the knit.”

Shop the new Boboutic knitwear collection at Santa Fe Dry Goods

Line is the Actual Experience

“I have my pace and way of living, and I’m not looking for something.”

“Each line is now the actual experience with its own innate history. It does not illustrate — it is the sensation of its own realization.”

“I think of myself as a Romantic Symbolist.”

Rundholz Black Label Spring / Summer 2018 Collection

Péro by Aneeth Arora Spring Summer 2018

Textiles as the Beginning

Textiles are an intrinsic part of fashion. For Péro by Aneeth Arora, it is incredibly important, because it is often the starting point. As a textile graduate from the National Institute of Design (of Ahmedabad, India), Aneeth Arora goes to great lengths to create the fabrics used in the Indian fashion line.

As part of the first step, Péro works with artisans from Chanderi, Maheshwar, West Bengal, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and more, all who handloom and dye the fabrics for each collection. After all, the Indian tradition of handcraft is emphasized throughout the design process. Because of Aneeth’s textile background, the textiles are developed with great care. In fact, the textiles, garment sewing, and handmade details all follow the traditional practice of passing through many skilled hands before completion.

Spring/Summer 2018

For spring, we see lightweight materials, such as cotton, linen, and silk. Florals, stripes, and gingham are combined and used throughout the SS18 collection. The feminine colors such as natural and creams, red, and accents of pink contrast the dark navy blue.

Familiar voluminous shapes are seen using these new colors, yet with new added details. These have become part of Péro’s language of approachable style, which is both feminine and cool. New details, all handcrafted and attached, such as embroidery styles also are included in this season. Limited edition and one-of-a-kind pieces have unique embroidery and embellishments. On the other hand, other pieces have dainty floral embroidery and knotted thread details on the gingham grid.

Shop the latest Péro by Aneeth Arora collection online

The Trajectory of Patchwork in The Quilts of Southwest China

Among the cluster of museums atop Museum Hill, tucked away from the Santa Fe Plaza, an artful curation of folk and applied arts from all over the globe can be viewed at the Museum of International Folk Art. The recent Quilts of Southwest China exhibition takes an intimate look within the contemporary realm of patchwork, focusing on traditional quilting among small communities (such as the Zhuang of Guangxi) in Southwest China, and the new life that is being returned to this dwindling practice by younger generations of Chinese artists.

Chinese ethnic minority bed and bedding, created for Quilts of Southwest China exhibition by staff at the Mathers Museum of World Cultures, Indiana University.

It is clear that the realm of patchwork is where artistic meets functional. Scraps are often repurposed, resulting in beautifully weathered mixed-prints. An inherent sense of vintage is imbued into each piece. Within the applied art of household textiles, duvets and other bed linens, tapestries and clothing for special occasions can be cut from the same cloth, mended and crafted in the same fashion.

Bedcover, c.2010s. Sha Sha (Hui). Kunming, Yunnan Province, China.

Bedcover, c.2010s. Sha Sha (Hui). Kunming, Yunnan Province, China.

Collection of the Yunnan Nationalities Museum.

Looking closely at this Bedcover from ca. 2010 quilted by Hui artist Sha Sha, the vivid color blocking is formed in the alternation between 52 blocks of natural-toned cotton and 52 blocks of brocaded, geometric designs. Traditional patterns and symbolism are built into each stitch. Thinking sartorial luxury, this textile brings to mind the iconic geometrics prints of Dries Van Noten, or Péro’s strong use of appliqué and embroidery techniques — in fact, Aneeth Arora discusses her travels to rural China as part of her inspiration for Péro’s FW17 Collection.

Péro by Aneeth Arora

Péro by Aneeth Arora

Left: Bedcover, after 1970s. Miao. Gulong, Huangping County, Guizhou Province, China. Collection of the Guizhou Nationalities Museum. Right: Bedcover, 1970s-1980s. Buyi. Lipo County, Guizhou Province, China.

There is often use of emblematic symbolism stitched into these quilts. The symbols reference ancestral histories or regional myths. On the left, a detail of a textile dating to the 1970s-80s and originating from the Guizhou Province of Southwest China iconographically captures a dance; this dance references a legend about the birth of clouds; a tree cut down and the transformation this gives life to; the role animals play in the ancestral stories of the Miao ethnicities. An appliqué technique was used here that involves mounting a paper drawing onto a piece of fabric, where the shapes of the drawing are then cut from the cloth and intricately placed onto a fabric substrate. On the right, the ancient sartorial technique of embroidery using fine threads is featured in this Buyi quilt, which also dates to a similar time as the quilt featured on the left.

Top Left: Prada SS17 Mandarin Collar Suit | Photograph by Gio Staiano | Courtesy of NowFashion. Top Right: Woman’s Jacket, 1900-1950. Yi. Malipo County, Yunnan Province, China. Quilts of Southwest China | Museum of International Folk Art, IFAF Collection, FA.2006.59.5. Bottom Left: Etro SS13 Silk Dress | Courtesy of Fashion Magazine. Bottom Right: Woman’s Woman’s Jacket, 1900-1950. Yi. Northern Yunnan or Southern Sichuan Province, China. | Quilts of Southwest China | Museum of International Folk Art, IFAF Collection, FA.2006.59.2.

Top right is a Yi women’s jacket; this article of women’s clothing dates back to the first half of the 20th century and is from the Yi of the Malipo County. It features the same patchwork piecing and embroidery techniques used in the quilts that surround it. The high Mandarin collar and the use of silk material is parallel to the styles we see in the current fashion industry. On the bottom left, The Miao women’s festival garment features an asymmetrical neckline and a robe / silk wrap dress quality that are also being used in modern cuts.

The Quilts of Southwest China exhibition in particular sheds light on the history of patchwork, as well as its current use among artists living in rural communities of Southwest China. It illuminates the history of how quilting techniques used in the realm of home textiles crosses over into textiles worn for dress, and how traditional motifs find a place in contemporary fashion.

Top: Mieko Mintz | Bottom Left: Greg Lauren | Bottom Right: Woman’s Jacket, c. 1984. Small Flower Miao. Near Guiding, Guizhou Province, China. Quilts of Southwest China | Museum of International Folk Art, gift of Phila L. McDaniel, A.2004.5.1. Photo by Carrie Haley.

Top: Mieko Mintz | Bottom Left: Greg Lauren | Bottom Right: Woman’s Jacket, c. 1984. Small Flower Miao. Near Guiding, Guizhou Province, China. Quilts of Southwest China | Museum of International Folk Art, gift of Phila L. McDaniel, A.2004.5.1. Photo by Carrie Haley.

The role of quilting techniques in our contemporary fashion industry is ongoing; these techniques took explicit form in patchwork styles, popular in the sixties and seventies. Patchwork, among other motifs drawn from traditional quilting practices have surfaced recently in the more subtle iterations such as altered denim, Japanese boro, mixed prints and recycled fashion. We see this in pieces from Greg Lauren and Mieko Mintz. The relationship between these current trends and the traditional quilting practice in the arena of the handmade is fascinating.

Denise Betesh’s Ancient and Modern Aesthetic

New Denise Betesh

New Denise Betesh jewelry is available to shop online. Because she is fairly new to our store, we have been slowly adding new pieces from the local Santa Fe designer. The new collection includes handcrafted necklaces, earrings, a ring, and a pendant. As usual, her pieces are expertly crafted with 22K gold and precious and semi-precious gemstones.

Her Materials Used

Denise uses 22K recycled gold, conflict-free diamonds, and ethically sourced gems. From imperial topaz to chinese aquamarine, her colors likely conjure imagery of the dreamy hues seen throughout the high desert landscape. As a result, the jewelry is truly enchanting. The matte finish, which is created from the process called “granulation,” is now a signature of Denise’s work. However, it was refined by the Etruscans, and has been used for thousands of years. In conclusion, Denise crafts jewelry that uses the best of ancient and modern techniques.

Shop the latest collection online

Sacai Spring/Summer 2018

Sacai Spring/Summer 2018

Chitose Abe has continued to build her unconventional and sophisticated aesthetic with the new Sacai collection. For example, the runway show included the signature controlled reconstructive designs. Her use of exquisite pattern mixing, slicing, and modern femininity was certainly well received.

Her expertly created chaos was held together by belts and sleeves tied across the chest. Because colors were combined so elegantly, even pieces with multiple layers, patterns, and textures were cohesive. Chitose Abe adds choppy and uneven pieces of fabric that peek through in different layers, which is probably her approach to the ruffle trend. On one hand, prints such as florals and plaid were frequently used, while vertical stripes were made with mixing different colored textiles spliced together into one garment. On the whole, the collection remained fresh but consistent; this is likely due to her design process.

Ready to Wear

Santa Fe Dry Goods + Workshop carries a selection of garments from casual tops to stand out pieces, which highlights the versatility of Sacai clothing. Specifically, a standout piece is a green and teal linen and polyester top with western influences. From a green linen yoke, satin teal pleats fall elegantly down the body. Rather than being over the top, the linen is finished as a raw frayed seam. Her western influences were more explicit in the Menswear Spring/Summer 2018 runway show. Yet, the runway shows that unisex designs have steadily growing in fashion.

Second, the embroidered heart lace top with fringe is another notable piece. Paired with the wide leg denim pants, the style is both edgy and feminine. In fact, any of the tops can be used in similar styling. No garments are boring; this is true for any piece. At first glance, a button-shirt is normal except for its pleats subtly hidden by its stripe print, or a lace drawstring is the hem. The wearer can use these trick-of-eye surprises for versatile styling.

Shop new Sacai clothing online

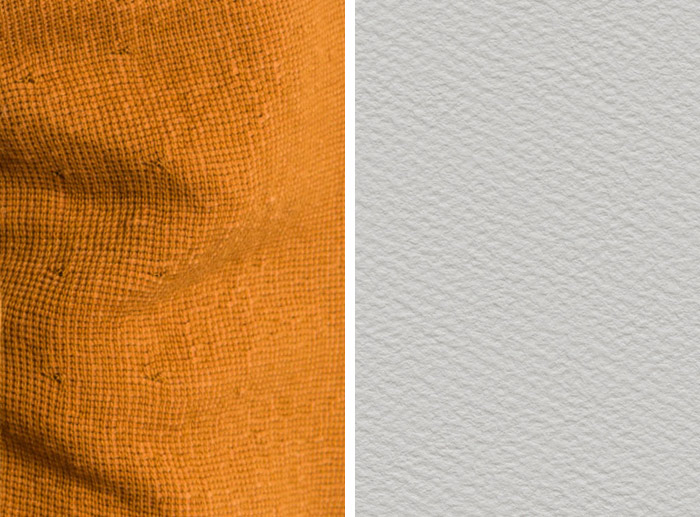

Different Textures of Shi Cashmere

Shi Cashmere Spring/Summer 2018

New pieces from the Shi Cashmere Spring/Summer 2018 collection are available online. The oversized and simple geometric shapes combined with use of minimal yet distinct textiles, have become a signature for the brand. This season is no exception, with materials such as breathable linen, distressed cotton denim, and textured polyester.

This season uses a simple and approachable palette of white, black, natural beige, indigo blue, pastel pink, and powder blue. The usual smooth textiles such as woven linen are uses in the round neck tops. However, we also received two pieces with new textures. The “window” textile has two layers of fabric embroidered together, with the top layer cut to create alternating panels that open and close freely. The other texture, used in a pair of pants, is a blue cotton denim weave with small distressed patterns, almost resembling speckles.

Etro Spring/Summer 2018 Has Arrived

Etro & The Tree of Life

Spring/Summer 2018 marks the 50th anniversary of Etro, which began as a textile design company in 1968 by Gimmo Etro. Since then, Veronica and Kean Etro have become the heads of womenswear and menswear collections. As a celebration, the siblings worked together in a combined women’s and men’s collection fashion show.

The Italian fashion house has, since its beginning, been heavily influenced by Indian textiles and others from around the world. Specifically, the paisley has become a signature. In fact, it remains a continuous inspiration, with countless variations. While the company continues to expand upon the versatile motif, this season was the about the Tree of Life. Starting as a date seed, the tree grows in both directions with deep roots and high branches—a beautiful analogy of the company’s history.

Etro Ready-To-Wear

Drawing from the lineage fascination with multiculturalism and diversity, Etro pays tribute to India this season. As always, their exceptional quality and elegance are combined to create their bohemian luxe aesthetic. The ready-to-wear line integrates these core values with soft, dusty hues or rich vibrant colors that pop against a black background.

Shobhan Porter, owner and buyer, usually makes a deliberate and artful selection of garments to sell in the store. As a result of her curation, we have cashmere/silk jacquard scarves, silk paisley printed scarves, intricate floral and paisley blouses, floral embroidery and contrasting fringe. The paisley and floral jacket with tie-closure detail is a standout piece, being both rich in details and aesthetically cohesive.

For this season, Santa Fe Dry Goods is introducing their shoes to our stores, starting with two styles of sandals. First, we have a ruffle slingback sandal in black, which is versatile and classy. For those with a playful style, the silk slip-on with a leather base comes in a royal blue.

Shop the new collection online or in-store at Santa Fe Dry Goods.

Inside | Out Vol. 2: Embroidery – The Craft of Two Hands

Historians may never know when embroidery first came into being, but it is safe to say that as long as people have been making clothes out of fiber, they have also been embroidering them. The sewing techniques people use to make, tailor, mend, or reinforce clothes also opens a world of possibilities to decorate and embellish them. The first solid records we have of embroidery are as far back as 500 BCE China and 300 CE Sweden.

Embroidery most likely emerged from the Levant, where gold thread was used to lavishly decorate the royal robes of the Persian emperors. The art form then made its way into China and then slowly entered Northern India, which today is the nexus for this art. The first place embroidery really took hold in India was Kashmir. As we emerged into the Common Era, specific kinds of embroidery sprouted up all over India. Each one is specific to the region it is from—we get Chikankari from Lucknow, Kantha from Bengal, Phulkari from Punjab, Aari from Kashmir, and Shisha from Rajasthan and Gujarat.

With this absolutely colorful history, it is no wonder designers like Aneeth Arora of Péro and Dries Van Noten chose to work closely with Indian communities to preserve the wonderful skills of these regions and instill their clothes with an artistic mastery like none other. Embroidery is not only beautiful to look at but it gives each item a sense of uniqueness that feels both warm and personal.

Embroidery is an art that can be found worldwide. It has been used as a sign of wealth, as a sign of individuality, or even as a sign marking a girl’s path into womanhood. It has been a sacred source of income for farmers in the winter time and one of the few historical sources of income available for women until about the 19th century. It has also been a community event, where women get together to simultaneously embroider, relax and socialize. With each motif created on a piece of cloth, a story is told.

Long Nv San Jiu, a fourth-generation tin embroiderer from the Guizhou Province in China states:

Travel with us as we explore the different types of historical embroidery specific to certain regions of India:

As an honored gift to his allies, Zahiruddin Babur, the first founder of the Mughal Empire would give a sumptuous set of clothes to mark the partnership. The gift would include a turban, long coat, gown, fitted jacket, sash, shawl, trousers, shirt, and scarf. Each item would be woven from the goat fur of the region (also known as cashmere) and embroidered with gold-thread. This ancient type of gold embroidery, originally from Persia, is called Zardozi and is a favorite today by Indian Brides and is used for any garment that needs that extra royal touch.

In 1568 CE Babur’s grandson, Mughal Emperor Akbar conquered Kashmir. The Mughal emperor Akbar was a huge fan of a beautiful aesthetic. So, along with fostering the production of cashmere (or Kashmir) shawls, he also fostered the art form of embroidery, setting up royal workshops in Lahore, Agra, Fatehpur, and Ahmedabad. Kashmiri embroidery draws its inspiration from nature, mostly featuring birds, flower petals, vines, lotuses and trees. It only uses a simple chain stitch and was first mostly seen as a white thread on a white or off-white cloth; today Kashmiri embroidery can be extraordinarily colorful, but still uses the original chain stitch. Today we call this embroidery from Kashmir either Kashidakari or Aari.

Just below Kashmir, on the northern point of India, is the region of Punjab. Punjab is known for their embroidery style called Phulkari. Its name literally means flower-work and usually features complete flower motifs. As the common embroidery of “country” folk, it is characterized by elaborate floral motifs entirely covering a modest hand-spun cloth—no space on the cloth is spared. Historically, it was primarily used as a pastime by women of the household, but today it is used by Indian fashion designers as a purposeful design element.

Next we go to the northeastern city of Lucknow in Uttar Pradesh, where the common form of embroidery is called Chikankari. It is said that the Mughal Emperor Jahangir (who ruled after Akbar) is responsible for fostering this style of embroidery in this region. It is very similar to Kashmir embroidery, where the motifs are nature based and a white thread is used on white muslin or cotton, but Chikankari uses more complex stitches such as buttonhole stitches, french knots, running stitches and shadow work. The patterns are created by block printing the motif on the fabric, and then stitching over the pattern.

Traveling to the Bay of Bengal, we go now to West Bengal where the most common form of embroidery is called Kantha. Closely related to the Japanese form of embroidery called Sashiko, Kantha embroidery involves long running stitches that bond two or more sari fabrics together. A utilitarian yet intimate practice, Kantha is traditionally sewn for loved ones as an intricate and personal keepsake. It is also a modest form of embroidery, usually used to reinforce fabrics that are wearing out or to make something new out of old pieces of cloth.

The embroidery most commonly associated with India is called Shisha and it is from the western regions of Rajasthan and Gujarat. Shisha originated from Persia and is also called mirror-work. It involves using uncountable tiny, interlacing threads to sew hundreds of little mirrors onto the fabric. This embroidery is usually seen on items such as bedspreads and pillows.

This deeply folkloric artform touches hearts because it translates a sense of beauty that is deeply human. It takes time and patience to create, and is simply transformative—both for the sewer and for the garment.

Inside | Out Vol 1: Defining Quality Cashmere

Cashmere yarns are the fiber of choice for those passionate about soft and luxurious knitwear. This diamond of the knitwear world can only be found in a few specific regions: Mongolia, the Tibetan Plateau, and Kyrgyzstan. It comes from the domesticated goats that live in these high and dry grassland areas. Beneath their thick, coarse outer-coats of hair that protects them from the blowing winds, negative temperatures, and winter snows lies a soft and downy undercoat of fur, which is what we call cashmere.

This downy undercoat is a product of the goat’s evolutionary adaptation to the extreme winter conditions (the weather can drop to -58°F), making it one of the warmest and lightest fibers in the world. The longer the days and colder the weather, the longer and finer the goat’s hair will be, which is why these areas produce the finest and best cashmere in the world.

In spring, the goats begin to molt and shed their coats in anticipation of warmer temperatures; this is when the native herders begin the cashmere harvest. They shear off the coarse outer layer of hair and begin the painstaking process of gently combing out the precious undercoat of warm, soft hairs. The herders must time this combing carefully because if done too early, the cashmere is not ready to be shed, and if too late, it will fall from the goats and be blown away by the wind while at pasture.

The herders comb, wash, and hand sort the wool to remove any coarse outer-coat hairs. They then sort the fibers by length and size. The longest and thinnest hairs will be sold for a premium price. The thicker and shorter hairs will be made into less expensive garments and are often used as part of a blend with other fibers.

As you can see, the supply of cashmere is rather small—it accounts for only 0.2% of the total output of all animal fibers: it is restricted by geography, dependent upon mother nature, and the will and skill of the native grassland herders. It takes the hair from 3-4 goats just to make one sweater! This rarity mixed with a lengthy manual fiber-to-yarn process is what contributes to cashmere’s reputation of being truly a luxury item.

The fineness of a cashmere item comes down to the length (measured in mm), diameter (measured in μm—microns), and color of the hair collected from the goats (cashmere comes in three colors: brown, grey, or white; with white hair being the most valuable as it is the easiest to dye).

In order for the goat hair to be considered cashmere, it must be under 19 μm in diameter (human hair is on average 45 μm) and be at least 34 mm long. A micron is one millionth of a meter! The diameter of the hair is what indicates the softness—the thinner the diameter, the softer the fiber will be since it is less likely to push against the skin in a way that you will feel a prickle. Only the most uniform and longest fibers (longer than 36 mm) pass through an additional combing process to be converted into “worsted” yarn. Worsted cashmere creates a finer, smoother, and higher-quality yarn that produces a garment that is more lightweight and breathable.

The feeling of softness is also created by the scales and structure of the hair shaft. Cashmere fibers don’t have a medulla, which is a stiff, structural piece running the length of the hair shaft, common in sheep with coarse fleece. The nonmedullated (hollow) hairs of cashmere make it extra smooth, which translates as making it extra soft—and provides air pockets that add to its lightweight warmth.

The quality of the water where the raw cashmere is dyed and processed is also extraordinarily important to the final quality of the garment. During dyeing, the raw fiber is immersed into warm water for three hours, and the unique qualities of the water impart particular grades of softness onto the fibers. The alpine regions of Italy and the highlands of Scotland produce the finest cashmere in the world because of their unique freshwater lakes, such as Lake Como of Genoa, the alpine lakes of Biella, and Loch Leven in Kinross.

Cashmere is then generally spun into either single or double-ply thread. The ply denotes how many yarns are twisted together to make a single thread—two-ply means that two yarns are twisted together. It’s thought that the higher the ply is, the more durable the thread will be, since it is composed of more strands. Cashmere is spun into plies anywhere from one to eight. A cashmere garment woven with two-ply is usually considered plenty durable and not likely to get holes, and depending on the quality and reputation of the manufacturer, single-ply cashmere can be plenty durable as well, yet with an added ethereal quality.

Cashmere fibers can be compactly arranged during the spinning process, resulting in excellent warmth retention (typically 8 times that of wool) without adding bulk, which is why cashmere garments are uniquely breathable, warm, and comfortable. People who choose cashmere, do so because they know that it is one of the most beautiful fabrics that will last them a lifetime of use if cared for properly.