Don’t miss these premiere designers at this year’s edition of the International Folk Art Market (IFAM).

Program curated and moderated by Philip Fimmano. For more details visit folkartmarket.org/tickets.

2024 IFAM Speaker Series

In celebration of the 20th edition of the International Folk Art Market (IFAM), the annual speakers series takes its cue from the broad Indigenous worldview that time is cyclical and circular. In this context, a non-linear approach will be used to simultaneously discuss the past, present and future of folk art.

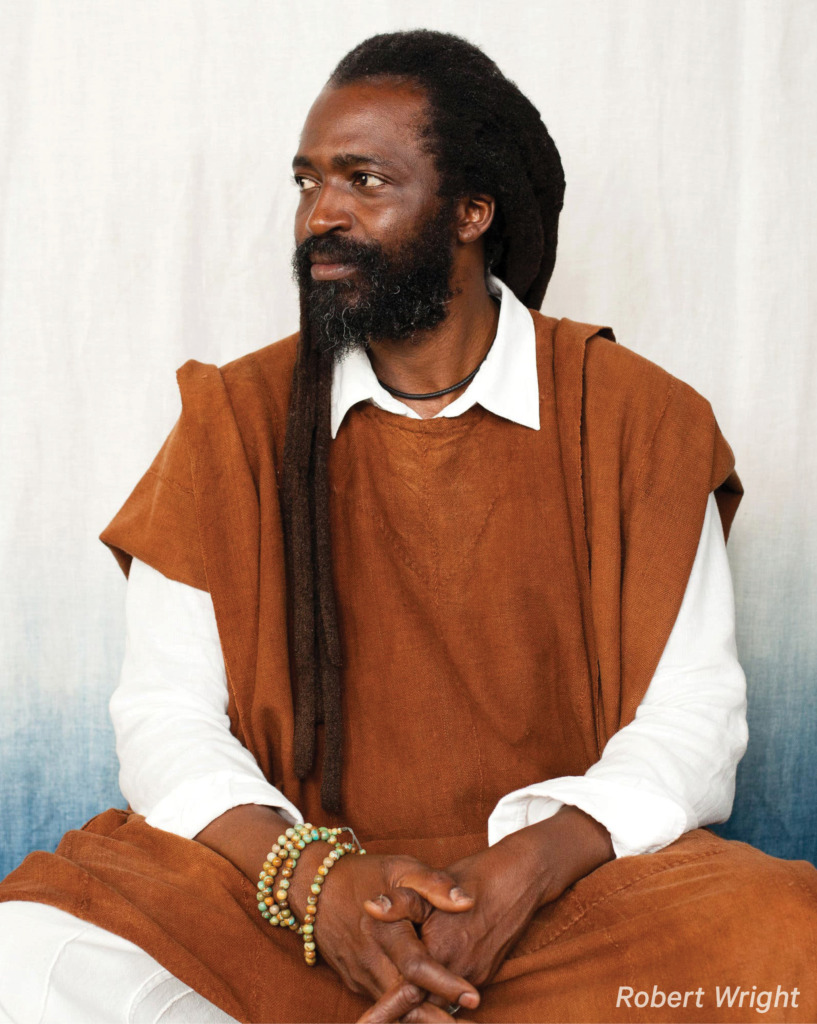

Friday, July 12 at 10am: Aboubakar Fofana

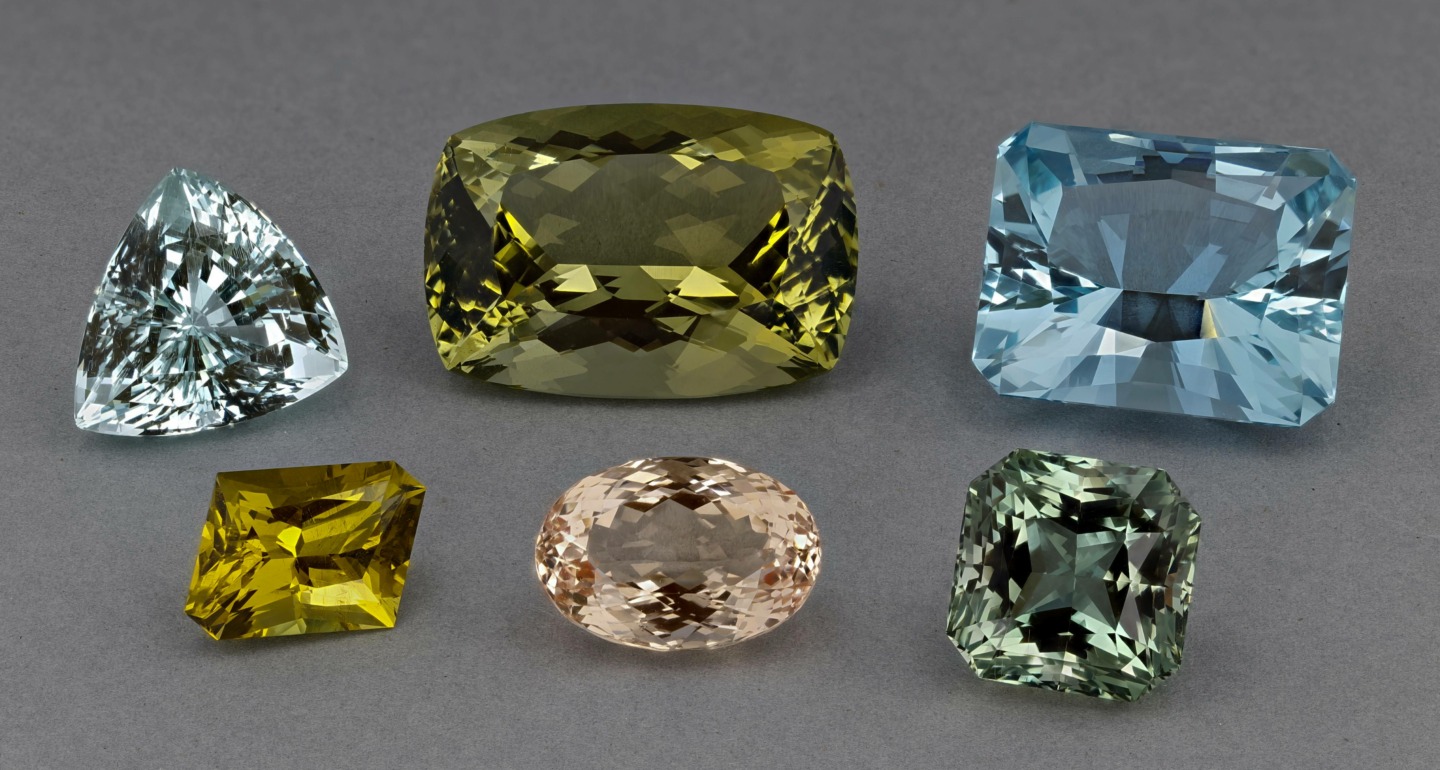

Born in Mali and raised in France, Aboubakar Fofana is a multidisciplinary artist and designer whose working mediums include calligraphy, textiles, and natural dyes. He is known for his efforts to reinvigorate, redefine and preserve West African textile and indigo dyeing techniques.

Aboubakar began his artistic journey with calligraphy, which lead him to wonder about traditions similar to this in Africa and to learn about natural textile dyeing. His work stems from a profound spiritual belief that nature is divine and that through respecting this divinity we can understand the immense and sacred universe. Aboubakar uses raw materials from the natural world, and his working practice revolves around the cycles of nature, the themes of birth, decay and change, and the impermanence of these materials.

Aboubakar is currently deeply involved in creating a farm in conjunction with the local community in the district of Siby, Mali, in which the two types of indigenous West African indigo will be the centerpiece for a permaculture model based around local food, medicine and dye plants. This project hopes to contribute to the rebirth of fermented indigo dyeing in Mali and beyond and represents Aboubakar’s greatest project to date.

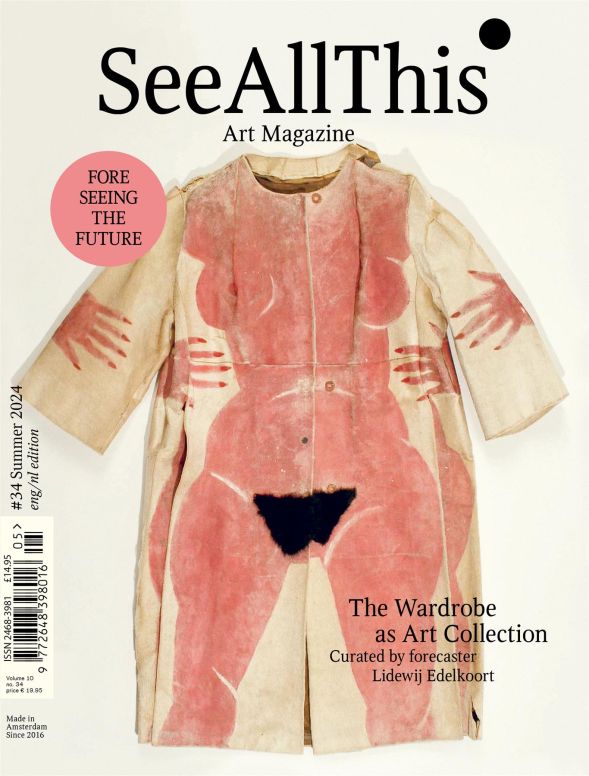

Saturday, July 13 at 2pm: Natalie Chanin

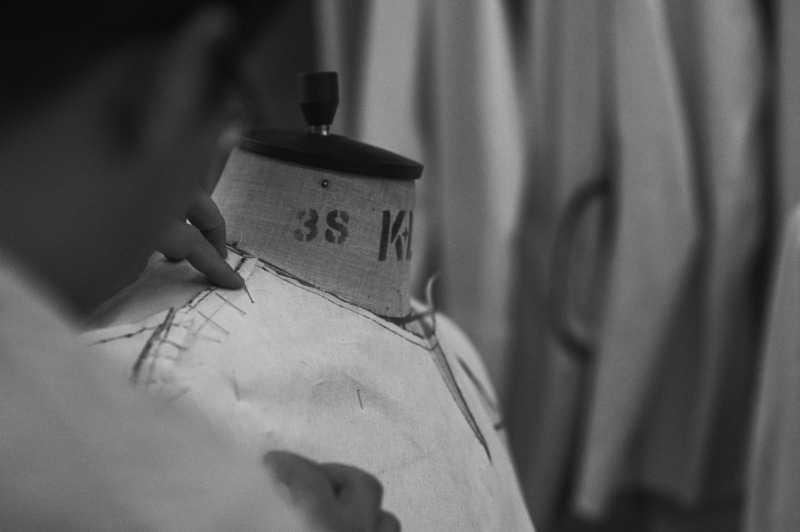

Founded by Natalie Chanin, Alabama Chanin maintains its headquarters in a former textile factory. Located in Florence, Alabama, the brand collaborates with independently contracted seamstresses and tailors, which has helped to revive the textile industry in the area.

Ultimately, the venture was inspired by Natalie’s Grandmothers. Growing up she realized that anything could be handmade, and the few store-bought items in her grandparents’ closets were made to last. For this reason, Alabama Chanin has been committed to sustainable design. They work hard to preserve handcrafted traditions while producing locally and ethically, with the highest possible quality standards.